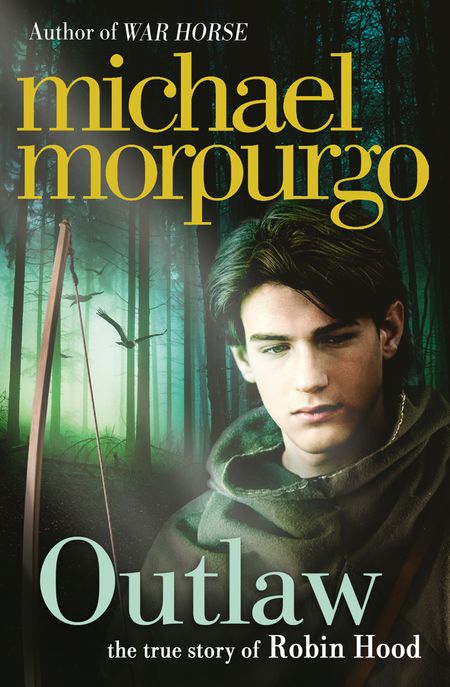

An interview with Michael Morpurgo was conducted and transcribed by Allen W. Wright. His book Robin of Sherwood was published in 1996 (with illustrations by Michael Foreman) and re-published in 2012 under the new title Outlaw: The Story of Robin Hood.

AWW: What versions of the Robin Hood legend most inspired you and why—both in childhood and in writing Robin of Sherwood/Outlaw?

MM: I went back to the early poem, probably 14th century and read the fits (verses) that tell the story. This was as close as I could get to even earlier versions, orally told, of which of course there is no trace. Early tellings are bleak, and end, not with Robin and Maid Marion (a later invention to sugar the pill) getting married in Sherwood Forest, but with the leaching to death of Robin Hood by a prioress. Knowing he was dying he asks his friend Little John to help him shoot his last arrow out of the window. Where it lands, says he, there you must bury me and plant an oak tree over my grave. It was from this ancient ending that I took the beginning of my story – the great oak, hundreds of years later, blown over in a storm, roots ripped up to reveal the arrowhead and bones.

[He is likely referring to the ballad A Gest of Robyn Hood which appears in several printed editions circa 1500 and contains many plot elements that appear in the modern legend. It concludes with a brief account of Robin’s death at the hands of the prioress. This was expanded in the ballad Robin Hood’s Death. Click here to read two versions of Robin Hood’s Death and the related section of the Gest. – AWW]

AWW: What do you think are the most enduring and appealing aspects of Robin Hood? What makes it unique from the many other legends you’ve explored in your books?

MM: I think the reason Robin Hood resonates all around the world, and many cultures have their own legends of such a folk hero, is because the fight against tyranny on behalf of the poor, the struggle against injustice and oppression, is universal in its appeal.

AWW: One of the things that struck me the most of about the book is how dark it could be. Violence, death and loss were a pervasive part of Robin of Sherwood/Outlaw right from the beginning with the storm and the fallen tree. Why did you emphasize that aspect of the legend? And how do you approach weaving those dark themes into a tale for children?

MM: It is of course not a children’s tale but a tale for everyone. Children though do understand right from wrong, and can readily see that oppression by the rich of the poor has to be resisted. The Sheriff of Nottingham is a bully. Children know about bullies just as grown-up children do, and we all know that in the end we have to stand up and fight for what we believe. Robin Hood in my story does just that. Such a struggle involves violence, it always has done.

AWW: The depiction of the “Merry Men” (Outlaws in the 2012 edition and Outcasts in the original 1996 edition) as actually physically distinct – such as an Albino Marion and hunchback Will Scarlett – is strikingly different from the usual versions. It has a dark fairy tale feeling to it, but also seems to touch on something else. How did you come up with this depiction?

MM: I came across the stories of the Cagots in South West France, a group of people very often distinguished by the whiteness of their hair, the foreshortened fingers and their lack of earlobes. Historically they were treated as a race apart. They even had their own separate door to come into church and sit separately, and they were made to live outside town walls. Throughout history in most societies there have been outcast groups like this, Gypsies, Jews amongst them. These have always been the most downtrodden, and it was therefore from such groups that I felt Robin would have recruited many of his supporters. Merry Men they were not.

AWW: Why the change in nomenclature – from Outcasts to Outlaws – in the different editions?

MM: I felt that in the first edition there had been too much emphasis on their being outcasts rather than Outlaws, actually it came to the same thing in the end, and I felt Outlaw was a more understandable way to describe them.

You can read the rest of this interview at www.boldoutlaw.com